The simulation component of our application allows user to access a free compute server for creating recharge metric maps from electromagnetic (EM) resistivity data and other auxiliary in-situ well data including sediment/rock type and water level.

From the GIS layer , you create (or select) a region of interest, then click Start Simulation button in the Simulation panel to start a compute server. Details of our data analytics tools can be found in Knight et al. (2018), Goebel & Knight (2021), and Pepin et al. (2022).

- Load Data

- Data Review & Co-location

- Rock Physics Relationship

- Review 3D Grids

- Generate Recharge Metrics

- Export Results

Each step is a Jupyter Notebook (or Lab) and we used ipywidgets for creating user interfaces. Below we well describe each of these steps in detail in the subsequent sections.

Inputs of the workflow are:

- EM resistivity data

- Sediment/rock type data

- Water level data

Outputs of the workflow are:

- Recharge metric maps and associated contours

- 3D Sediment type and resistivity models

- User defined variables

Load data¶

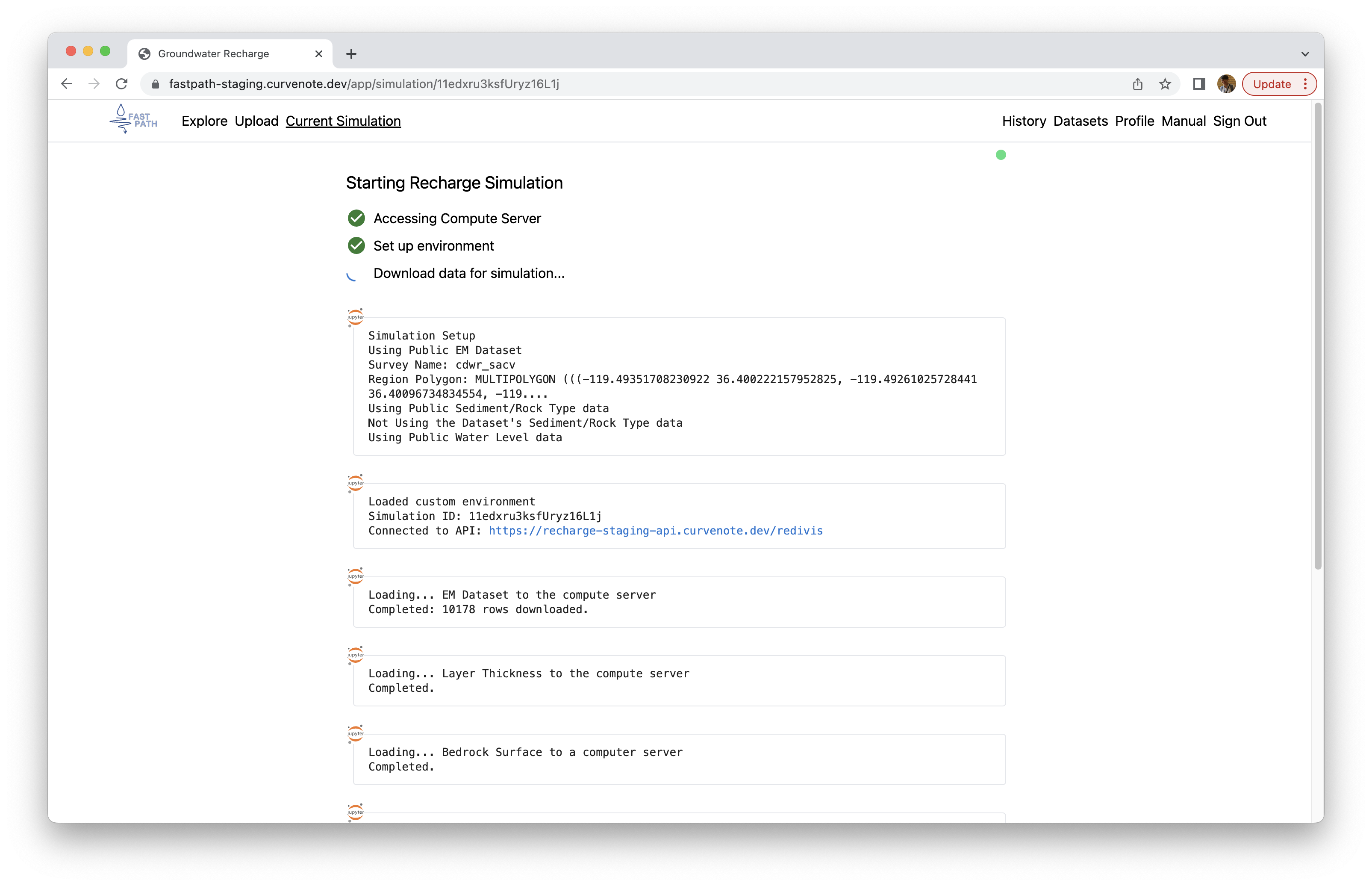

First step - Load data - is automatically executed right after clicking Start Simulation button in the GIS layer. You could identify progress of the data loading as shown in Figure 2. This could take about a minute. Once it is done, the app will progress to the next step: Data Review & Colocation.

Figure 1:Loading data from the online database to a compute server.

Data Review & Colocation¶

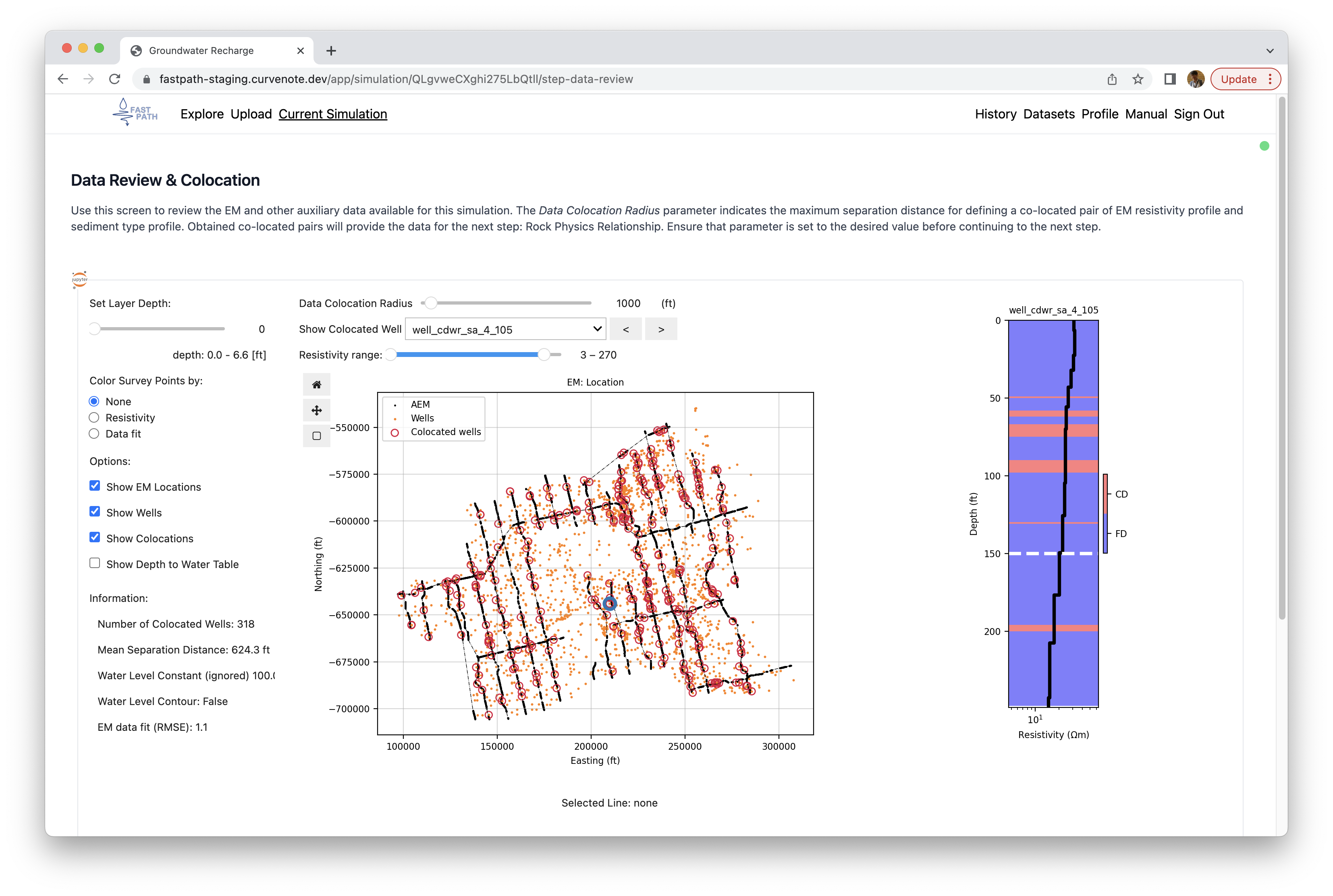

Second step allows you to review the loaded data including EM resistivity, sediment/rock type, and water level. While you can spend as much as time you want for reviewing the data, the only variable that you need to set in this step is “Data Colocation Radius”. The reason why we need to set this variable is to obtain colocated EM resistivity and sediment/rock type data to construct a relationship between resistivity and sediment type in the next step: Rock Physics Relationship.

Figure 2 shows an example view that you would see in this step. A default value for AEM data and tTEM data were set to 1000 ft (300 m) and 66 ft (20 m), respectively. These values were empirically determined based upon our experiments on groundwater subbasins. You are recommended to start with a default value, but we highly recommend to vary this value and see results in the next step to find a relevant colocation radius for your application. For choosing a relevant colocation radius, as colocation radius decreases, accuracy of the co-located data increases while available colocated data decrease. Hence, we need to seek for a sweet spot (i.e., colocation radius) that could provide the colocated data with accuracy and size. This process involves analyzing the resulting rock physics relationship in the next step with a variable colocation radius.

Once you set a colocation radius in our app, by clicking “NEXT - ROCK PHYSICS TRANSFORM” button at the bottom of the page.

Figure 2:Data review and colocation step allowing user to explore the data and set a relevant colocation radius.

Rock Physics Relationships¶

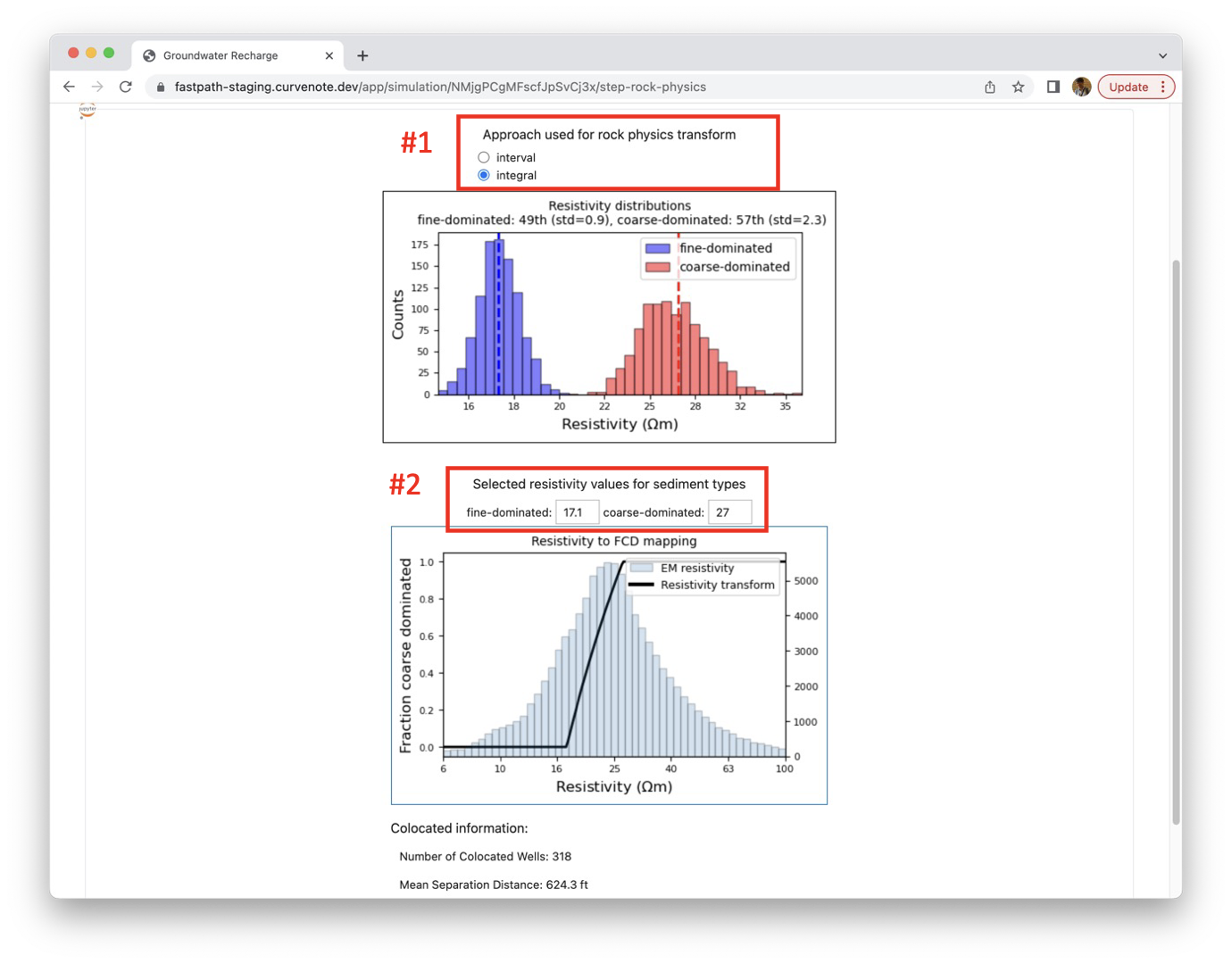

A goal of the third step is to build a relationship between resistivity and sediment type using the colocated EM resistivity and sediment type data. For this, we first estimate resistivity distributions for binary sediment types including fine-dominated and coarse-dominated. Then by sampling a representative resistivity value (default: 50 percentile i.e., median) from each distribution, we construct a mapping function that converts resistivity to fraction coarse dominated ranging from 0 to 1. Figure 3 illustrates this process to create a mapping function.

Figure 3:Results of rock physics transform. Top panel: resistivity distributions for two sediment types: find-dominated (blue) and coarse-dominated (red).

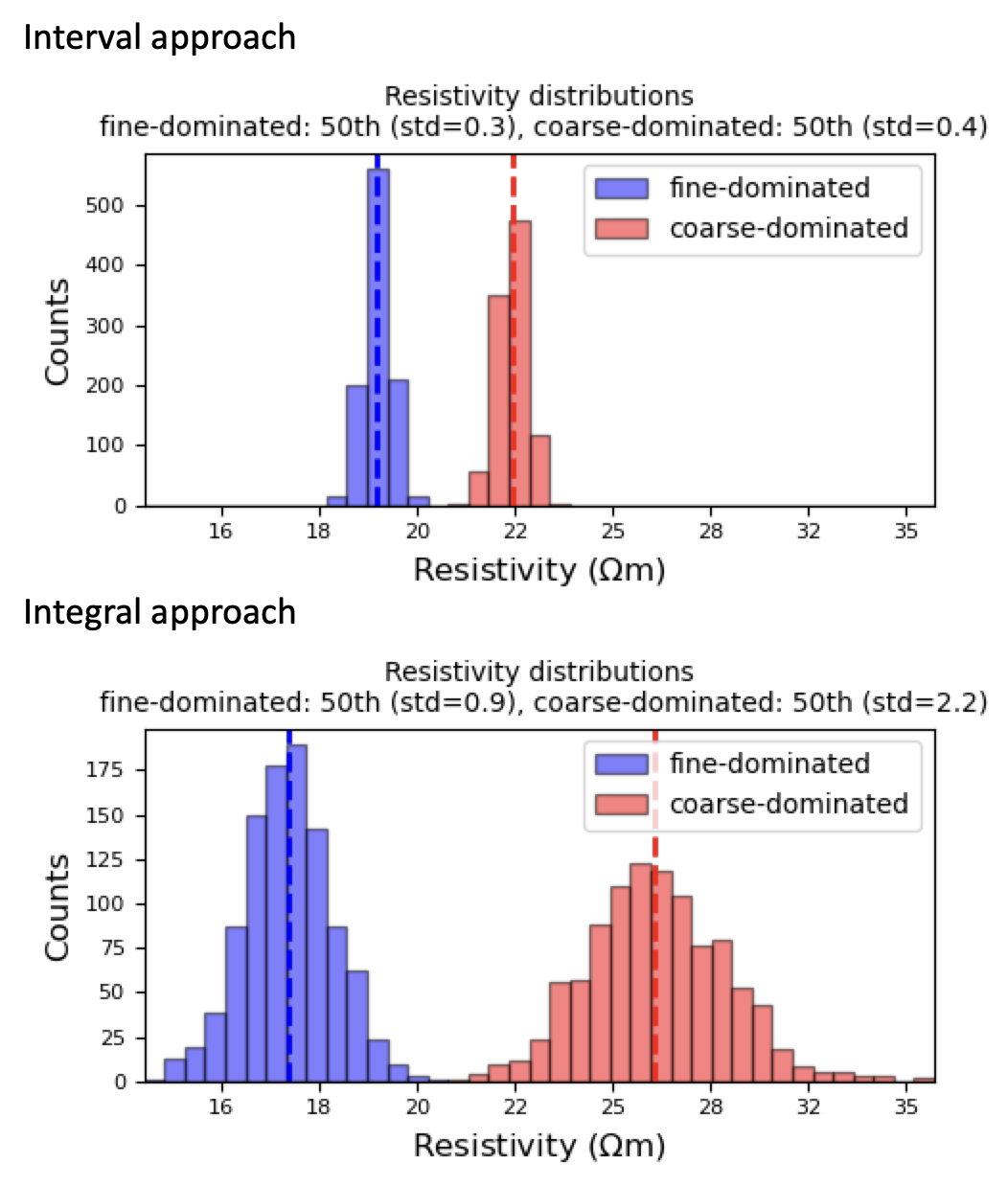

As shown in Figure 3 (#1 red box) , there are two approaches available for creating resistivity distributions including “interval” and “integral”. An interval approach uses each vertical cell of resistivity and associated sediment type data while an integral approach use average of resistivity values and that of fraction coarse dominated from an interval between surface to water table. For the basin-scale application using AEM data, we set the default option to be “integral” to take into account the limited spatial resolution of the AEM resistivity data. Figure 4 shows an impact of this option. Resistivity distributions from the interval approach has a tendency to show smaller variance than those from the integral approach. This is because of the greater number of colocated data for the interval approach. Difference between median values of two distributions from the interval approach is much smaller than that from the integral approach. This is because of the improved accuracy of resistivity and sediment type data with averaging process. Accuracy of EM resistivity data genuinely increases with increasing vertical interval, that is EM resistivity is very inaccurate at a very small pixel but more accurate at a larger vertical interval.

Figure 4:Comparison of resistivity distributions from interval and integral approaches.

For the local-scale application using tTEM data, we set the default option to be “interval” as there is generally much less colocated data. The number of colocated data drastically decreases if an option is changed from “interval” to “integral”. For instance, say we have 10 pairs of colocated data. For each pair, there are 10 vertical cells of resistivity and fraction coarse dominated data. Then for the “interval” approach, the number of colocated data is 100 while for the “integral” approach is only 10. So, where there are only a few sediment type profiles (or wells), then by using “integral” approach there is insufficient data to build probabilistic distributions.

When building a mapping function, we use simple parallel circuit model:

where is resistivity (m), is fraction (dimensionless), and subscripts and indicate coarse-dominated and fine-dominated. By rearranging (1), we obtain

(2) allows us to map a resistivity value to a fraction coarse dominated as shown in the bottom panel of Figure 3; here we also show histogram of the EM resistivity in the vadose zone, which we transform to fraction coarse dominated. You can also input resistivity values of coarse-dominated and fine-dominated with our app as shown in Figure 3 (#2 red box). Corresponding percentile values of resistivity distributions will show up in the top panel displaying resistivity distributions as shown in Figure 3.

Once a desired mapping function is obtained, click “NEXT - GENERATE 3D GRIDS” button to proceed.

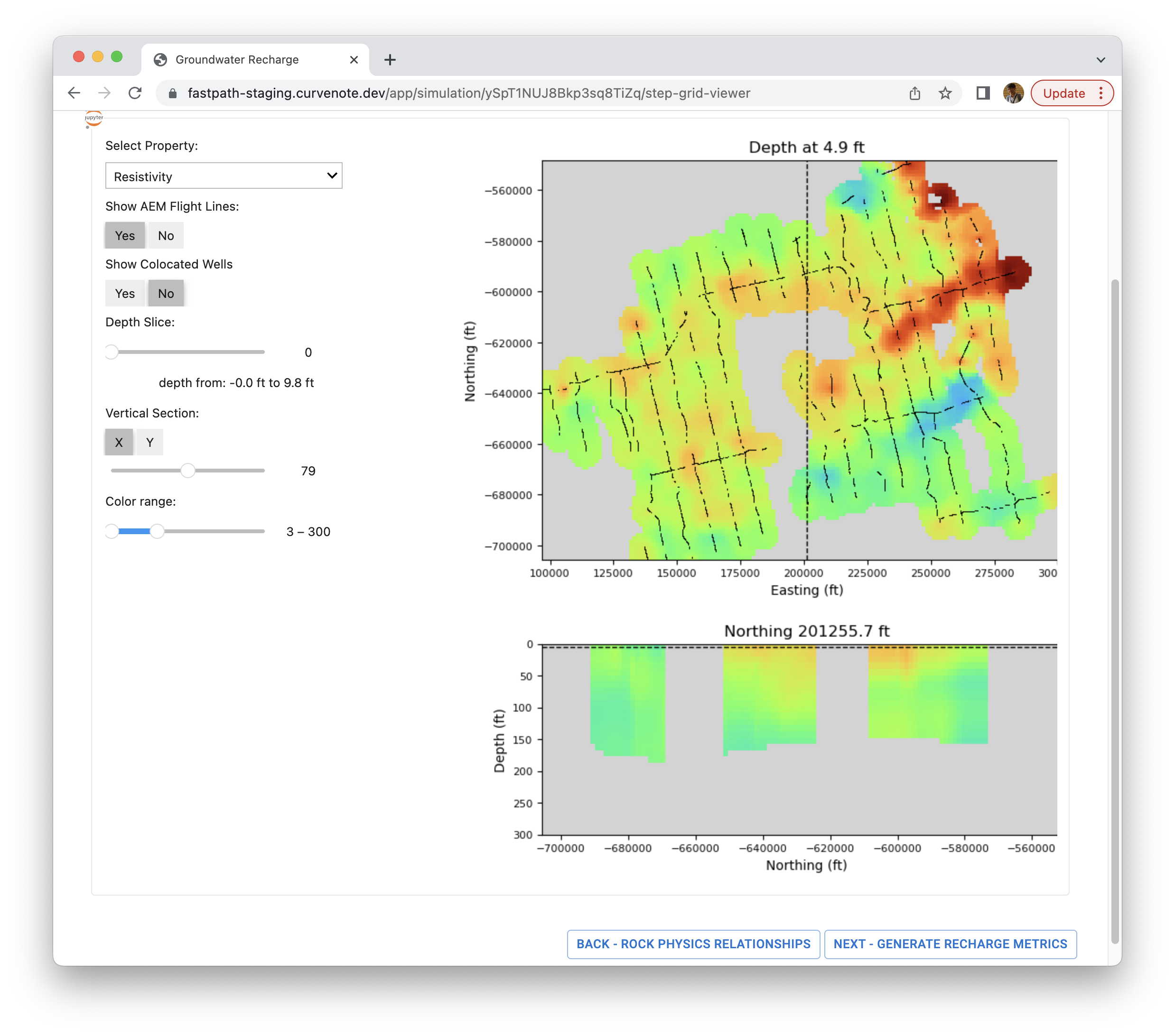

Review 3D Grids¶

In this step, 3D models of resistivity and fraction coarse dominated (FCD) sediemnts can be visualized and reviewed both as horizontal plane view slices at depth, and vertical section as shown in Figure 6. Under the hood, the application generate the 3D resistivity model on a regular 3D grid by interpolating the 1D EM resistivity profiles. Depending upon the EM data source (either AEM or tTEM), the uniform cell size uses will differ. For the basin-scale AEM, a uniform cell size of 400m400m3m is used while the local-scale tTEM uses a 20m××20m××1m grid. Lateral extent of the grid is designed to cover the EM resistivity data and vertical extent of the grid is designed to cover a vertical interval from surface to water table.

Using the mapping function obtained from the previous step, the 3D resistivity model is transformed to a 3D fraction coarse dominated (FCD) model. Depending upon the region of interest, the bedrock surface may be shallower than water level (e.g., in the foothills of Sierra Nevada). In such a case, resistivity values below the bedrock surface are removed (See Online database for how we interpreted the bedrock surface).

Figure 5:Review 3D grids. Horizontal plane view and vertical section of a 3D resistivity model are visualized in our fastpath app.

Once you got familiar with the resulting 3D models, and happy that they meet any existing understanding of the region of interest, you can move to the final step by clicking “NEXT – GENERATE RECHARGE METRIC”.

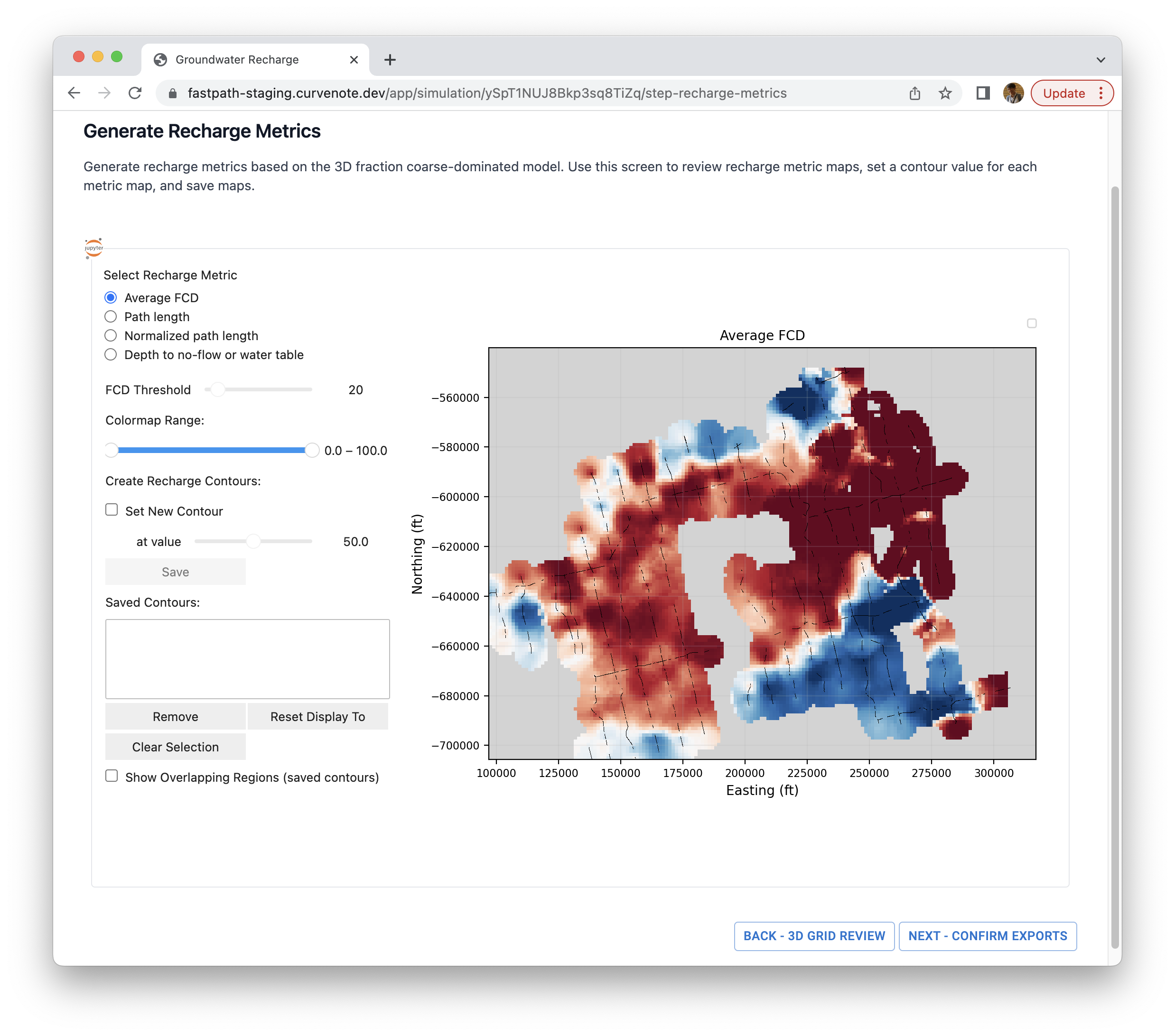

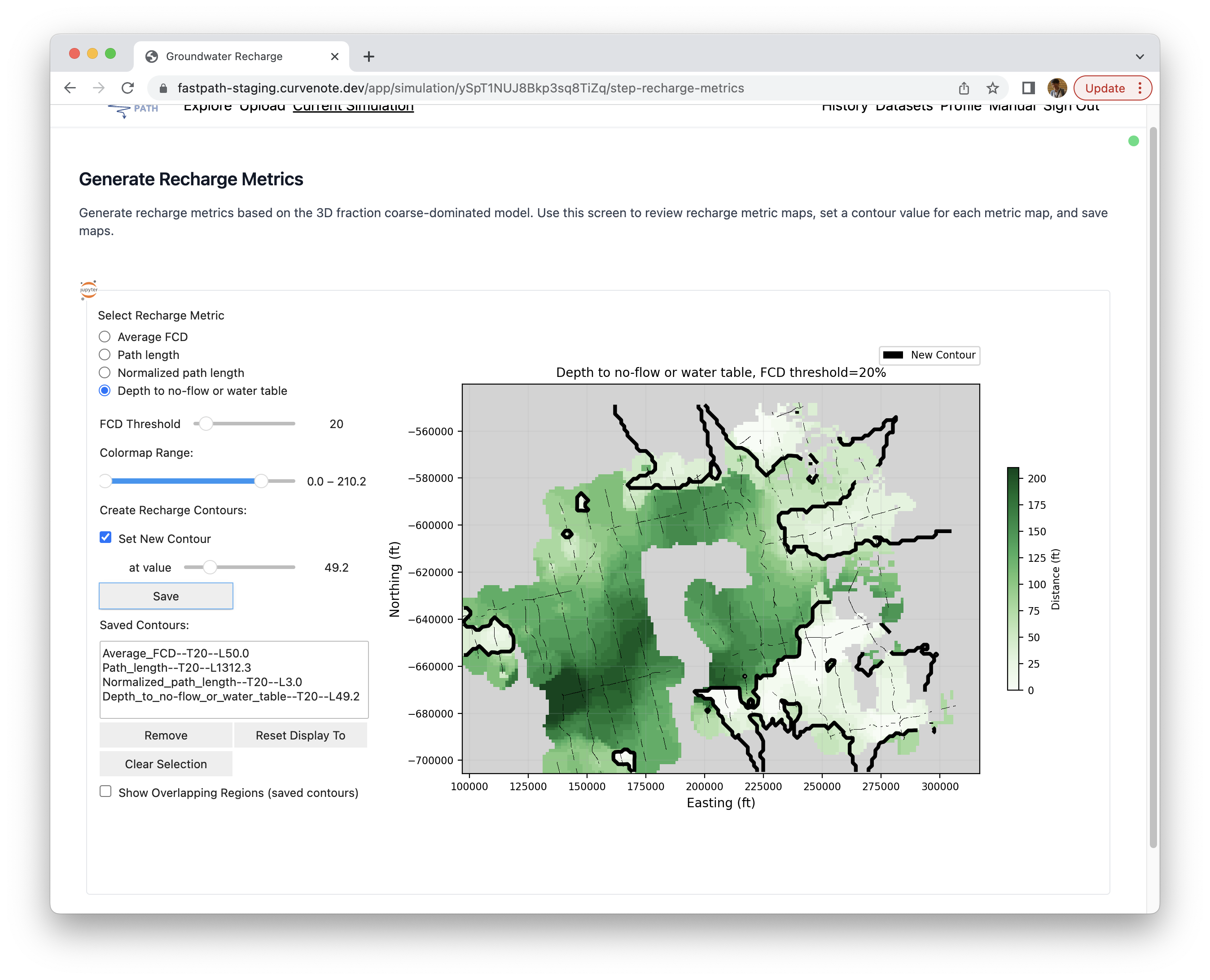

Generate Recharge Metrics¶

In this step four different recharge metric maps are generated (as illustrated in Figure 7) using the 3D fraction coarse dominated (FCD) model obtained from the previous step. These four metrics are:

- Average FCD: this is a vertical average of FCD values from surface to water table [0, 100%].

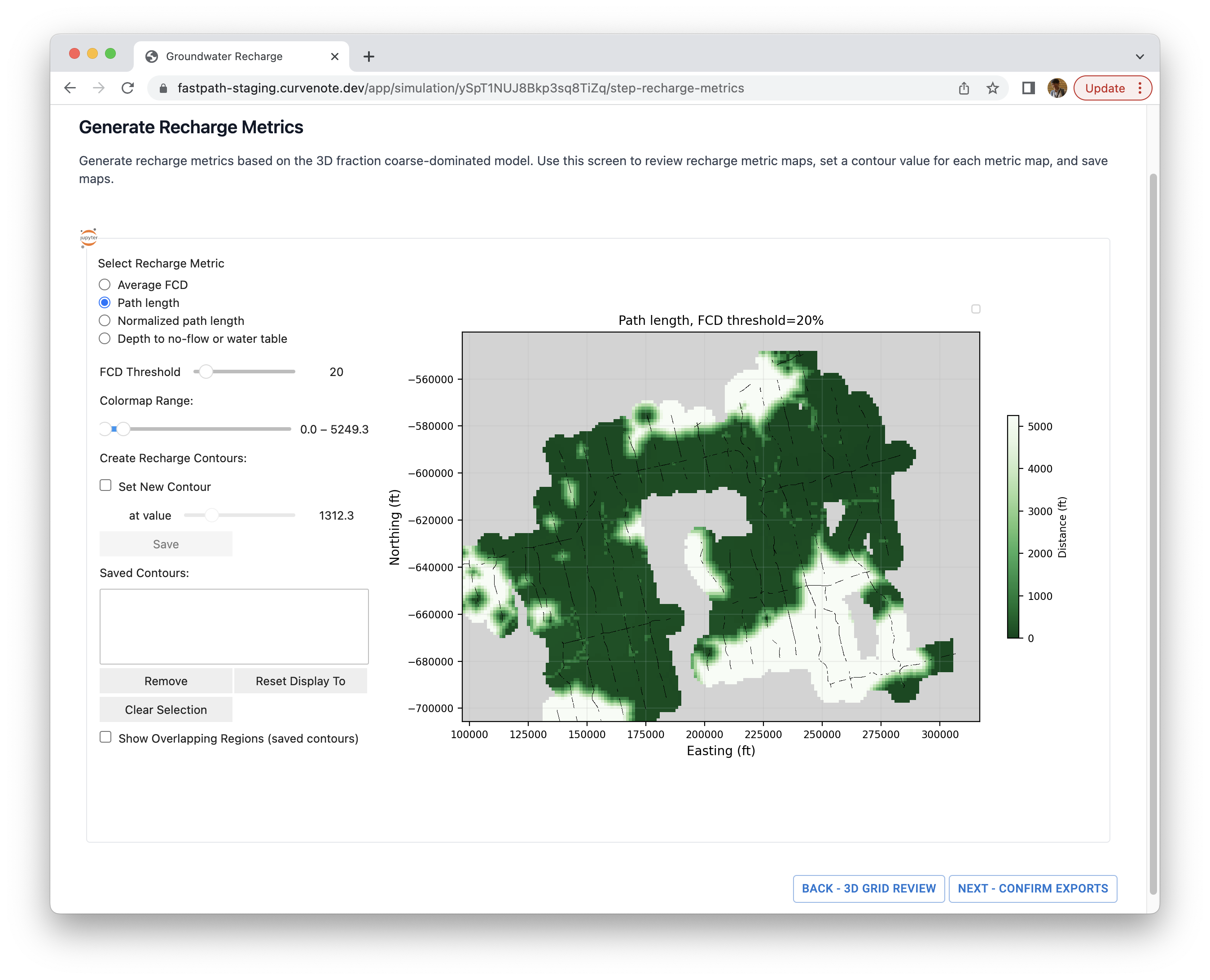

- Path length: this indicates distance between surface and water table through no-flow unit [0].

- Normalized path length: this indicates path length normalized by depth to water table [1].

- Depth to no-flow or water table: this indicates depth to the shallowest no-flow cell or water table (if there is no no-flow cells between surface and water table in vertical direction) [0, depth to water table].

For each metric sxcept for an average FCD map, the user must define what constitutes a flow/no-flow unit by selecting a FCD threshold (a toggle bar shown in Figure 7). For instance, if this threshold is set to be 20% then all FCD values less than 20% are classified to be no-flow and others to be flow. Therefore, increasing a threshold value will genuinely decrease areas with recharge potential.

Figure 6:Generate recharge metric maps. 2D map of average fraction coarse dominated (FCD) is displayed.

An average FCD map provides a first order information about the sediment type of the vadose zone. Greater the FCD value, the better for recharge. While the average FCD map provides integrated information about the sediment type in the vadose zone, this map cannot prevent the case where there is a thin clay layer at depth blocking the infiltration of surface water. A path length map allows us to take into account this case by finding paths from surface to water table through flow cells; the shorter the distance the better for recharge (See Figure 7). A normalized path length map provides a bit different insight given it is normalized by the depth to water table. It is like a tortuosity of the vadose zone. For instance, a value of normalized path length, 1, indicates a vertical direct path from surface to water table while that of 10 indicates that the path length was ten times greater than the depth to water table. Finally, a depth to no-flow map highlights where shallow clays or a shallow water table might result in ponding of water.

Figure 7:A path length map.

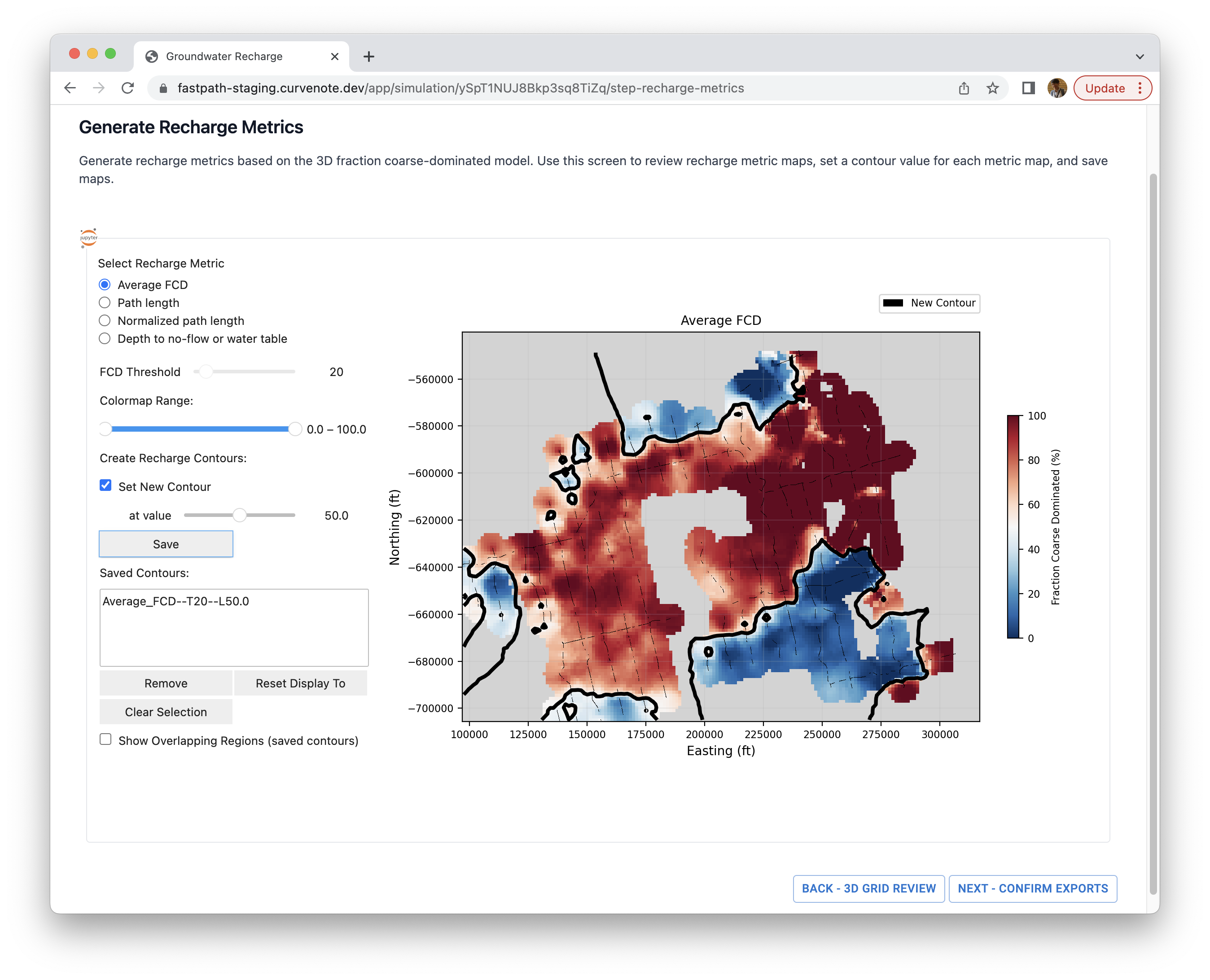

To guiding decision making, we provide contouring tools to draw boundaries for each metric map. For instance, you could set a 50% as a threshold value for an average FCD map to define a contour of interest. This could be implemented through our app by checking “Set New Contour” and selecting a value with a toggle bar - “at value”. If you want to save this decision boundary, than click “Save” button then saved contours will be listed in “Saved Contour” box. Figure 8 illustrates this process.

Figure 8:Defining a decision boundary for an average FCD map.

Similarly, you can select contours obtained from other metrics. For instance, in Figure 10, we selected a contour for each metric. Checking “Show Overlapping Regions (saved contours)” will display regions where all the contours overlap, indicating the site would be more suitable for recharge, as green color and other regions as white.

Figure 9:Selected boundary for each recharge metric.

Once your analysis is finished, clicking a button - “NEXT - CONFIRM EXPORTS” - will move you to a Session Export Summary page.

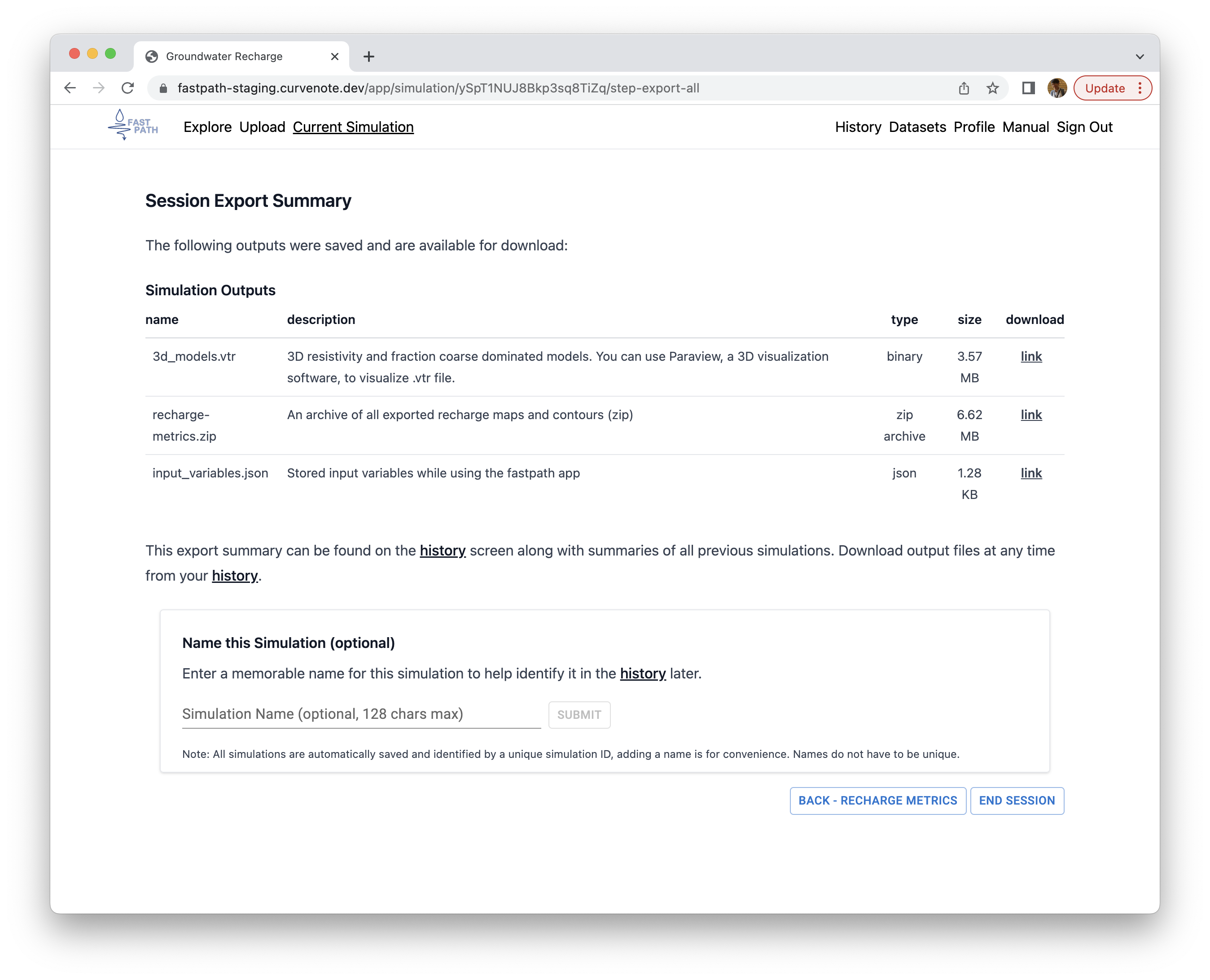

Data Export¶

Figure 10 shows an example session export summary page. There are three files available for you to download under the Simulation Outputs:

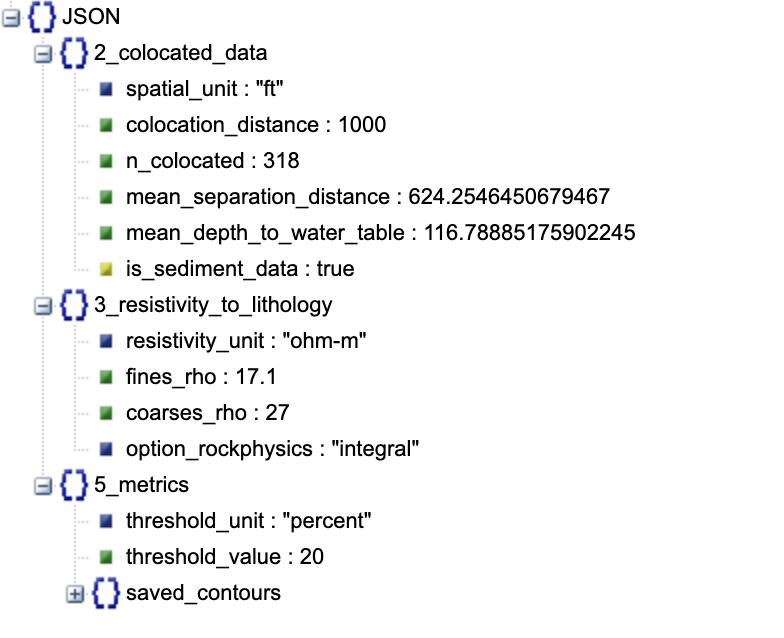

3d_models.vtr: 3D resistivity and fraction coarse dominated models. You can use Paraview, a 3D visualization software, to visualize .vtr file.recharge-metrics.zip: An archive of all exported recharge maps and contours (zip)input_variables.json: Stored input variables while using the fastpath app

You can also name this Simulation as illustrated in the bottom part of Figure 10.

Figure 10:Session export summary page.

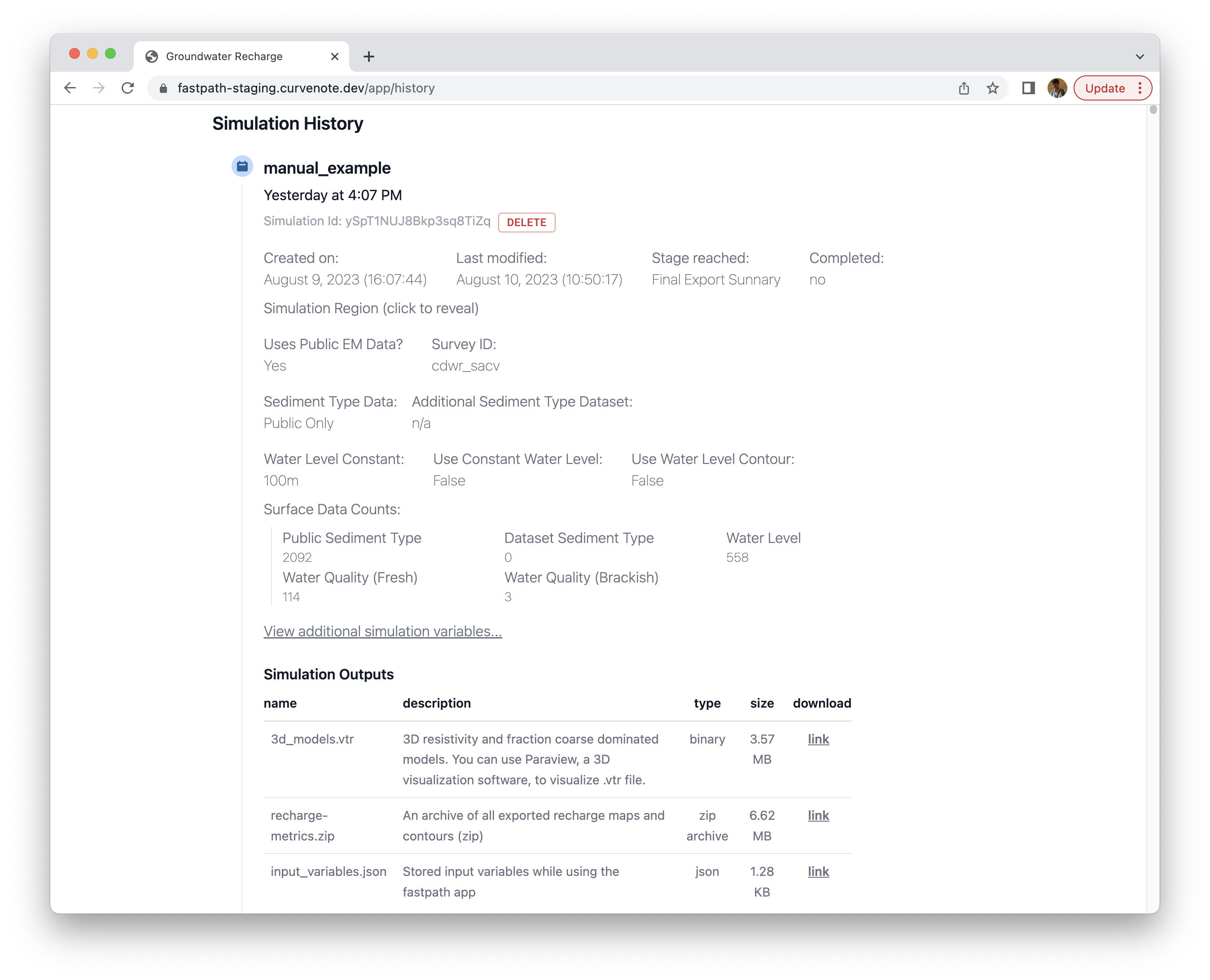

Once you end the session, the stored simulation will be displayed through the “History” tab. Figure 12 shows an example Simulation History stored in users’ account. The simulation outputs from this session will be stored and accessible for a short period (days).

Figure 11:History tab displaying stored simulation results.

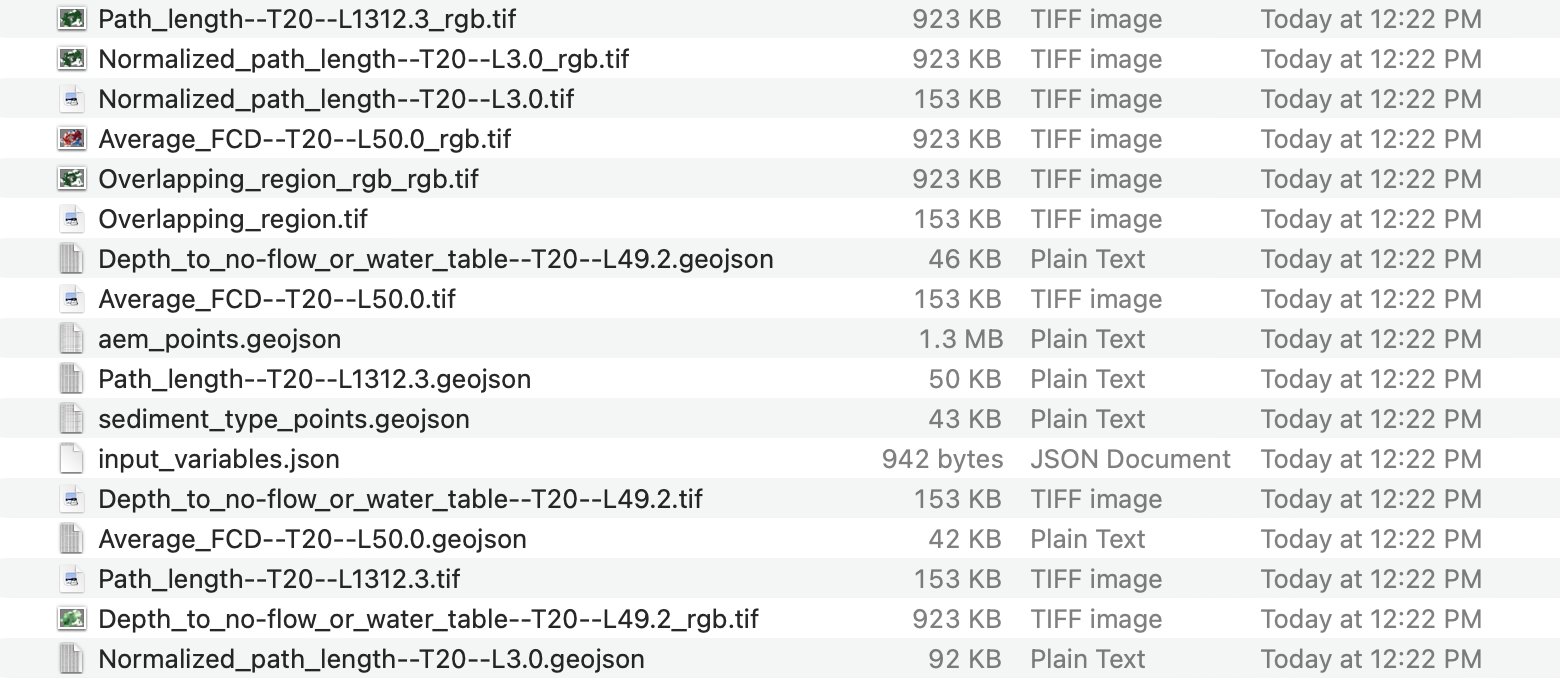

Let’s expand the last two files including recharge-metrics.zip and input_variables.json. Starting with a zip file, Figure 13 shows the list of files obtained by unzipping the compressed zip file. There are two different file formats:

.geojson: stored contour lines (i.e., decision boundaries based upon your choice of a threshold value)..tif- if a file name does not include

rgb, then it is a single channel tiff file containing values of a recharge metric map. - if a file name includes

rgb, then it includes RGB channels that is, an image is stored in this file.

- if a file name does not include

Figure 12:List of files obtained by unzipping a recharge-metrics.zip file.

A file name provides useful information, for instance:

Path_length--T20--L1312.3.tif

Path_length: metric type is path length.T20: a selected FCD threshold is 20%L1312.3: a threshold value used to define a decision boundary for the path length map is 1312.3 ft.

The other file is input_variables.json.

For visualizing this file, you could use a json file viewer (e.g., https://jsonviewer.stack.hu/). An example view is provided in Figure 13. Important parameters that you have chosen throughout the use of the app are stored and available through this file. This will allow you or other people to reproduce your results.

Figure 13:Visualization of input_variables.json file.

- Knight, R., Smith, R., Asch, T., Abraham, J., Cannia, J., Viezzoli, A., & Fogg, G. (2018). Mapping Aquifer Systems with Airborne Electromagnetics in the Central Valley of California. Groundwater, 56(6), 893–908. 10.1111/gwat.12656

- Goebel, M., & Knight, R. (2021). Recharge site assessment through the integration of surface geophysics and cone penetrometer testing. Vadose Zone Journal, 20(4). 10.1002/vzj2.20131

- Pepin, K., Knight, R., GoebelSzenher, M., & Kang, S. (2022). Managed aquifer recharge site assessment with electromagnetic imaging: Identification of recharge flow paths. Vadose Zone Journal, 21(3). 10.1002/vzj2.20192